Unchain the Imagination: A Call to Arts

We are on the verge of creating new cities, ones that are no longer addicted to fossil fuels. Let’s take this chance to question the absurdities that have become norms of current city life. We invite you, the artists, makers, designers to come up with ideas for the city of the future and let your imagination run free!

New York, summer of 1939. The world is on the brink of war, yet there is no sign of slowing down at the World Exhibition. An optimistic and savvy segment of the population shows the potential behind technology, and its impact on future life. Top attraction: Futurama, a sneak peek into 1960’s U.S.

Futurama is a diorama, the size of nearly half a soccer field. The pavilion consists of 500,000 houses and a million trees. The objects start in miniature, but grow in size until one sees houses and trees at the scale of 1 to 1. At the time of the exhibition, car usage in the United States is still relatively limited, but Futurama shows a different angle: a web of highways with no less than seven traffic lanes, and a strict separation between living and working. It is impossible to live in Futurama without a car. During the Exhibition, five million people visit Futurama. At the exit, everyone receives a button that says ‘I have seen the future’.

Dreaming of the car

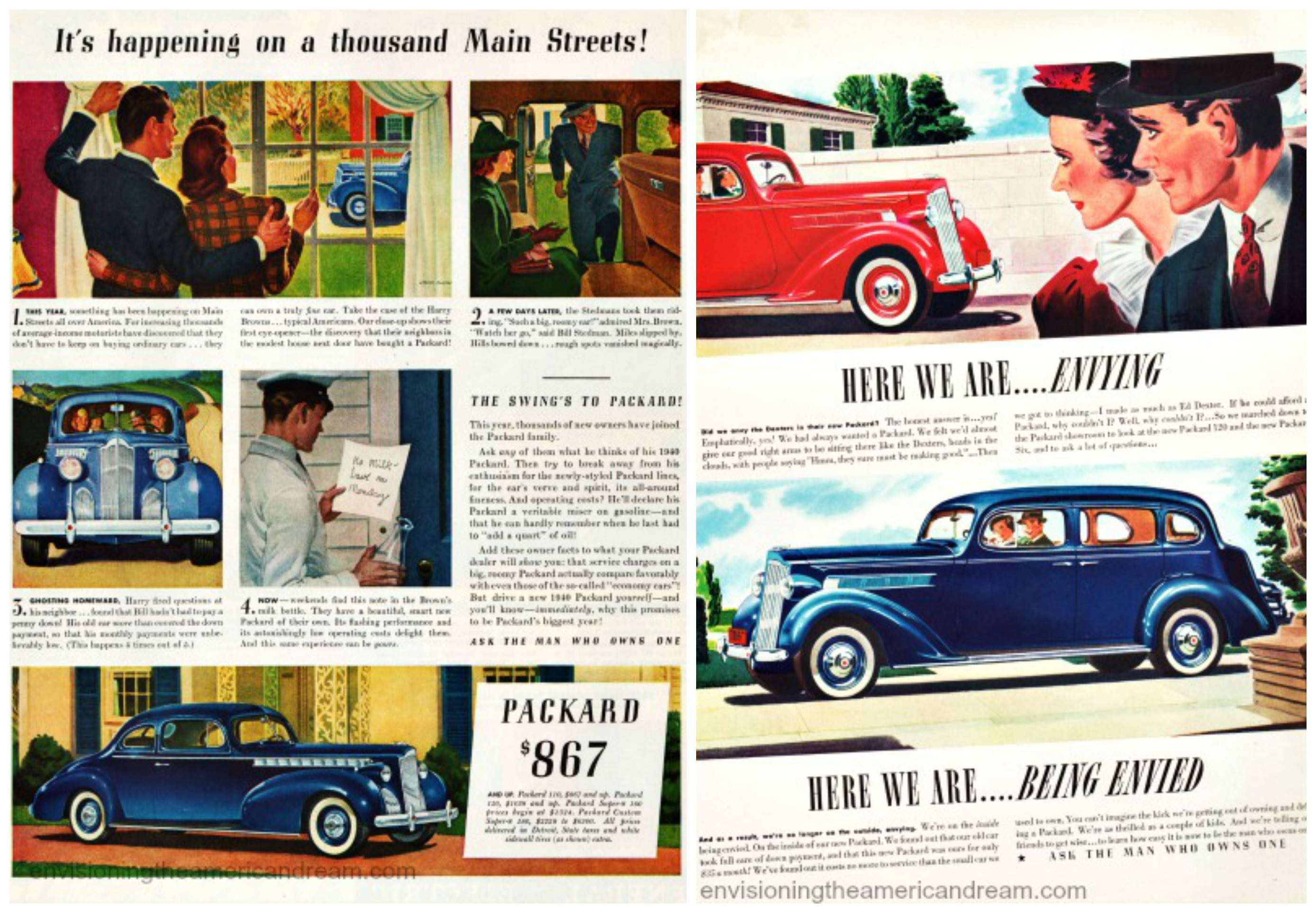

Futurama's sponsor and initiator is General Motors (GM), a car giant hailing from Michigan. There is no surprise that the car is self-evident in this imaginary. "Here we are, envying", a jealous couple muses in a 1937 advert of car brand Packard, while staring at their neighbours' car. Then, in the picture below, now in a gleaming car themselves: "Here we are, being envied." The car is not just a product, but necessary for a happy, full life:

"Unimaginable", we'd say when it comes to an idea that seems completely impossible. The opposite is true, as well. If an abstract idea becomes easier to imagine, it also might approach in the nearer future. Futurama and the car adverts of the past sketch a future in which it becomes possible for everyone to own a car, and life without this necessity is hardly worth living. In the words of Don Draper, of Mad Men:

"Happiness is the smell of a new car. It's freedom from fear. It's a billboard on the side of the road that screams reassurance that whatever you are doing is okay. You are okay." [>]

Futurama gives shape to a desire that did not exist before. Car adverts do not merely show the future, they shape it as well. The imagination of designer Norman Bel Geddes and countless other commercial designers brings a specific future within reach. The world of the car becomes imaginable, desirable and ultimately, reality. And the city adapts itself to it.

A City Made for Speed

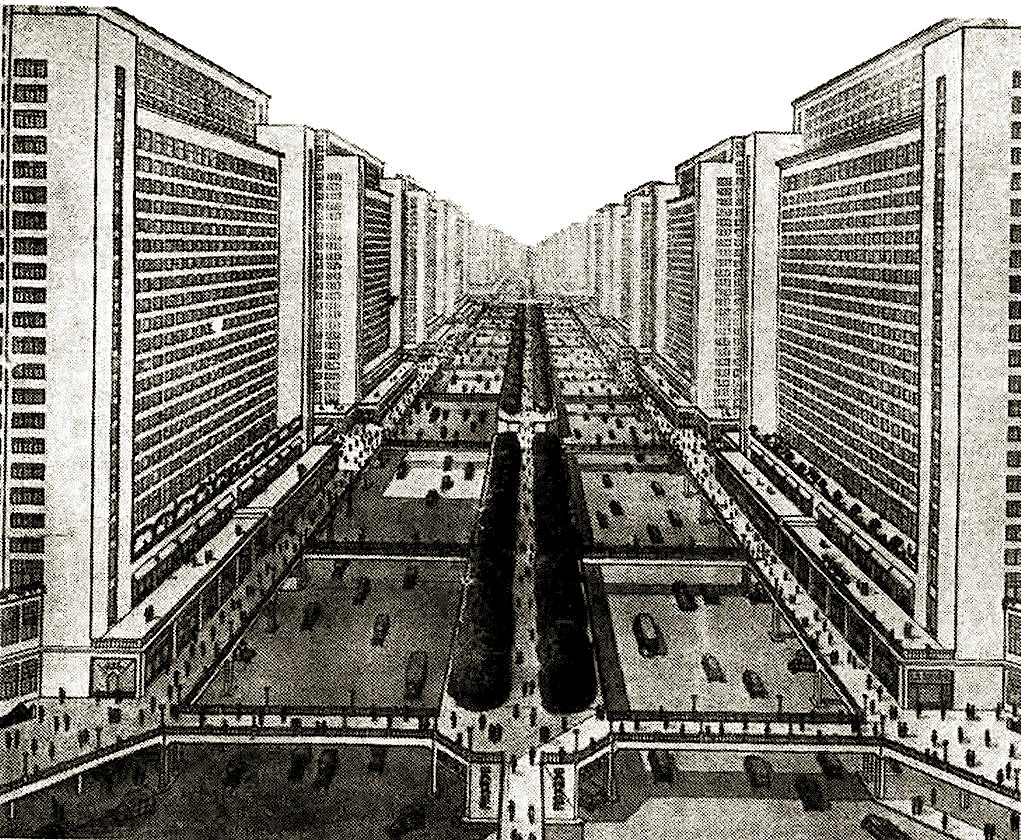

"A city made for speed, is made for success", argues the influential architect Le Corbusier as early as 1925. [>] He presents us with a city designed for cars. Le Corbusier abhors the idea of business men leaving their cars vacant or idle for public transportation that could get them to the destination sooner. Therefore, Plan Voisin keeps its various traffic flows strictly separated to promote fluidity, and even the way in which houses are built is to be based on the production process of cars. The city of Le Corbusier is a well–oiled machine, efficient and organized. Above all, it's clean: a tabula rasa, a city straight from the drawing board.

None of our current car adverts show people stuck in traffic jams. Glamorous images show shiny new cars driven gracefully through picturesque sites. The driver – nearly always a man – is a race car driver, who owns his vehicle. A recent video from BMW illustrates this perfectly. The car is hypermodern, self-driven and with talking abilities and follows a beautiful, empty road somewhere along the coastline of southern California. Admittedly, the video does mention a traffic jam, but the intelligence of the vehicle makes it easy to avoid the hold-up – in sharp contrast with the real life scenario where, for instance, in Los Angeles where traffic gets stuck for hours.

The Brittle City

‘It's the sense of touch. In any real city, you walk, you know? You brush past people, people bump into you. In L.A., nobody touches you. We're always behind this metal and glass. I think we miss that touch so much, that we crash into each other, just so we can feel something’. So describes a character from the movie ‘Crash’ the city in which he lives. Los Angeles: car city par excellence, embodying the imagination of Le Corbusier.

Brittle, is how Richard Sennett describes a city like Los Angeles. [>] A ‘brittle city’ is unable to react to change because there is simply no space for it. This applies to many cities nowadays: the life expectancy of a modern house is, at most, about forty years. Detailed, uniform planning is soon overtaken by reality and then the city is trapped in the infrastructure of the past - in an obsolete, concrete mold of roads, for instance.

But not everyone is prepared to accept the brittleness of the city. On the contrary: it is frequently argued that the city can provide a starting point for larger societal change. (see [1] of [2]. Urban policymaking is relatively flexible and pragmatic; city governors being ‘forced’ to act once the jig is up. After all, many practical problems are visible at city-level before they become noticeable in the rest of the country.

Interest group Osymosys therefore regards the urban introduction of the self-driving car as a chance to a flying start for a completely different world.In the future sketched by Osysmosys, we share mobility and have a different system of taxation, as well as basic income for everyone. In this dream, the self-driving car is a means to an end, that brings more equality, less pollution and more interaction.

The alternative, according to the interest group, is an utter nightmare. Even more one-passenger cars, combined with the loss of jobs and fewer revenues to keep the roads in good condition. In conclusion: a city becomes even more brittle.

Crisis of the imagination

"Let’s talk", ends the video of Osysmosys. "Please contact us." But that is where the problem starts. What, exactly, can we talk about?

It seems unlikely that Osymosys’ vision of the future will ever materialize. Ideals are beautiful, but they are not graspable, hardly even imaginable. That has to do with content, but also with form. Whereas BMW presents detailed renderings and videos, Osysmosys’ vision is merely a rough sketch.

The BMW city is not only easier to think about – closer to what is already well-known – but it is also given to us, ready-packaged and boiled down to the smallest detail. The interest group warns us that we need to prevent a nightmare, but the car manufacturer offers an alternative: a dream to strive for, just the way we’re used to.

In the BMW commercial, the car has acquired a different, smarter form. What is still familiar, is the way in which we use that car. After all, sales numbers remain equally important in a post-fossil future. No wonder then, that the American Dream remains firmly alive in car manufacturers’ commercials.

Less self-evident is that many images in movies, books, magazines and games are also rooted in an unsustainable way of life that is the romance of the car era, with its highway movies, air travels and green lawns.

'A speedy convertible excites us not because of love for metal and chrome, nor due to an abstract understanding of its engineering. It excites us because it evokes an image of a road arrowing through a pristine landscape; we think of freedom and the wind in our hair; we envision James Dean and Peter Fonda racing towards the horizon', remarks writer Amitav Ghosh.

Ghosh signals a crisis of the imagination: in contemporary literature, we find hardly any mention of climate change and the challenges that accompany it. Just like the brittle city, we are stuck in obsolete imaginations of the fossil era, and we are not even aware.

According to the writer, existing literary forms are not able to catch up with the challenges of our time. This is because, to a large extent, these literary forms have banished the unlikely: the coincidences that we accept in real-life, we tend to think of as unlikely in a book or movie, and even unexpected changes are not tackled anymore. This makes it challenging to find an imagination for what cities are facing at the moment. [>]

The city: Workshop for Change

Of course, there are many initiatives of thinking about a world that is no longer addicted to fossil fuels. Take Siemens, for example. This company is known for its domestic appliances, but currently primarily activates in urban infrastructure. Its most important intervention is The Crystal, a London-based museum with a permanent exhibition about sustainability in the city.

[>]

The video below gives Siemens’ view on the future city. The video shows three cities running on renewable sources - Copenhagen, London, New York. The city dwellers of the future are no longer individual consumers: everyone produces energy, and trades it in.

‘Individuals are important, but community is king’, the voiceover announces.

Siemens’ vision of the future is all encompassing, and thoroughly thought out. It makes the future city imaginable and tempting: its water is clean, its air quality is prime and, most importantly, its inhabitants are happy. Siemens’ appealing imagination gives us a push on the way towards a post-fossil era, similarly to how Futurama once brought us one step closer to what would be a city centered around the car.

And, just like Futurama’s audience at that time, we run the risk of becoming trapped: we see the city of the future, but our vision is guided nearly always by a specific, technological and corporate imagination.

You do not need to be a left-wing activist to deplore this.

Because exactly what makes a city real remains out of sight in such a technological imaginary: life on the ground with its public spaces and communities. The frustrating, yet inspiring city, where opposites can live next to each other; the city that does not and cannot materialize ready-mades from a drawing board, nor emerge spontaneously. This is the city of continuous change, with all the conflicts that accompany it - the open, resilient city.

The Open City

A resilient city is not the result of a detailed blueprint, but of a myriad of existing practices that can be easily overlooked. [>]. Simple things, like cycling, for instance. Cyclists in cities such as Amsterdam and Utrecht easily navigate the chaotic traffic. Only the tourists’ clumsiness is a reminder that this interaction is more intricate than it looks. In the open city, human contact is unavoidable: here, the streets are alive.

The 20th century city, with its emphasis on adaptability to mobility by car, might have been no more than a step in between. We might be very close to a new kind of city life, that brings about urban renaissance. That future is perhaps already visible in some places. An example is in Copenhagen, where new expensive bridges are being built for bicycles, and not cars. As well in San Francisco that is a living laboratory, and where many big companies now experiment with new forms of mobility (self-driving, electric and offered as a service).

Ghent experiments with the so-called ‘leefstraten’ (living streets), in which inhabitants decide to temporarily ban cars. This results in a new ordering of public space, with grass carpets, playgrounds for children and neighbourhood BBQs. A living street is not always established without conflict: some residents value the increase in playground space for children, while others complain about diminished accessibility and the stand-around-and-do-nothing appeal it brings to the neighborhood. Yet the experiment has gained world recognition, and has been replicated in several cities.

The living street is an example of the open city, but on a small scale. The question is whether it is possible to propose such a change for the city, as a whole. The open city does not emerge from a rendering or a detailed plan. On the other hand, a bottom-up initiative like those in Ghent and Amsterdam are not necessarily better for the city’s future than the imaginary of an international corporation like Siemens. To unchain the future, we need to search for widely different perspectives on the resilient city. But what does this look like in practice?

Unchain the Future

On April 20, 2011, a man starts to undress right in the middle of Tate Gallery. Once he is fully naked, he curls himself in a fetal position, keeps his hands before his eyes and waits. Two veiled figures come and stand at each side of him: both of them carry a jerrycan with the logo of oil company BP. They bow and start pouring, covering the man with a black, oil-like substance. This goes on for eightyseven minutes: one minute for each day of the oil leak in the Gulf of Mexico, which started exactly one year before.

The performance, Human Cost, is an initiative of the group Liberate Tate, which protests against BP’s sponsoring of Tate Gallery. It results in an iconic image: an 'oil victim' on the marble floor of a prestigious museum, a growing oil stain. Suddenly, the problem surrounding fossil fuels is no longer limited to faraway, largely invisible places: it is right here, in the center of the city, the heart of culture.

"The imagination is today a staging ground for action, and not only for escape", wrote Arjun Appadurai. [>] When listening to the preparations for this guerilla performance, for which oil had to be smuggled into the museum, it is difficult to disagree. [>] At the same time, the performance raises a broader question: can artists help us to imagine the experience of a post-fossil city, or is art, too, caught up in existing stories?

An open, post-fossil city cannot be designed on the basis of a uniform Futurama. Once one accepts this, one suddenly sees tens of initiatives concerned with possible futures for the city. Naziha Mestaoui projects virtual trees in the city, growing on the rhythm of visitors’ heartbeats. A smart forest in the middle of the city. For each virtual tree, a real tree is planted somewhere on earth. [>]

Eve Mosher draws chalk lines through cities, to make high water lines literally touchable. Doing this, she enters into conversations with citizens who have never even entered a museum.

The Museum of Fossil Fuels collects objects that symbolize the transition to a post-fossil society: a plastic inhaler, a SUV, a puzzle about the story of oil. These initiatives allow us to question the absurdities of everyday life, to open a conversation and unchain the future– and, together, they provide us with a broad palette of possibilities for the post-fossil city.

The art of not-knowing

The artist is, more than others, used to working with the unexplored, the unknown. In the words of writer Donald Barthelme: "The not-knowing is crucial to art, is what permits art to be made. Without the scanning process engendered by not-knowing, without the possibility of having the mind move in unanticipated directions, there would be no invention. (...) The not-knowing is not simple, because it's hedged with prohibitions, roads that may not be taken." [>]

Exactly the abibility to deal with the unknown is important when designing an open city. Resilience does not result from a blueprint, but from the art of dealing with uncertainty. An incomplete form offers citizens the chance to give meaning to spaces, and allows for adaptation. A city without a fixed narrative is able to react to sharp twists in history. In the words of Sennett: "All good narrative has the property of exploring the unforeseen, of discovery; the novelist's art is to shape the process of that exploration. The urban designer's art is akin." [>]

The transition to a post-fossil era is the moment to sketch a new vista. The city does not ask for a linear narrative, but craves for an expansive, light-footed imagination. It is an exciting voyage of discovery. Now, on the eve of unknown changes, we need artists more than ever, to explore the roads that are not usually taken. To imagine the agile cities of the future.